EGYPTIAN BRACELET

From the Tomb of Tutankhamen – A New Discovery

Kent P. Streaver, Ph.D., FNAS, GAA, DMv

New archaeological discoveries can be the result not only of careful research into what has been found within the literature and artifacts of ancient civilizations, but also of equally careful research into what has been lost and not found. Of course, the extensive experience and the broad knowledge base that I have developed are essential for success.

The background to this exciting discovery began several years ago while I was traveling in Egypt under the auspices of a generous grant from the Imhotep Foundation. [1] The story of the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb always held great fascination for me, and I was eager to use Carter’s work in the Valley of the Kings as starting point for new exploration. The discovery of the submerged ruins of Alexandria was inspirational, and I began my search for clues under water in the Red Sea. Although I did not find any significant artifacts during that search, I was fortunate enough to meet several Egyptian colleagues who shared my interests and helped me navigate the challenging logistics of archaeological research at sites in the Red Sea and throughout Egypt.

Although I felt on the verge of an important discovery, this year’s research in Egypt was beset by difficulties, from the Foundation’s fiscal problems [2] to the demonstrations in the streets of Cairo and subsequent political revolution. And yet, it was those very demonstrations that led to the subject of this paper.

I was visiting the Cairo Museum in the new year of 2011, where I presented my credentials in order to review archival documents that might aid my quest. Suddenly all within the Museum rushed out into Tahrir Square, where the mass of angry, yet soon to be jubilant, humanity was overwhelming. Left alone, fearing for the safety of the artifacts in the museum, I started searching for safe storage areas where I might be able to hide the most valuable pieces from looters. I found myself in the depths of the lowest basements, at a small storage space that seemed to have been overlooked for decades. As I opened the door, the dank smell of antiquity that escaped convinced me that no person had been in this room in recent memory. I heard voices, footsteps above, the sound of breaking glass – all I could think of was finding a safe place for the museum’s treasures. I stepped into the room and quietly closed the door. With my ear pressed against the door listening for the looters, my hand found a light switch. Pushing the switch on, a dim glow from an ancient light bulb permeated the room, and I heard an ominous scratching sound behind me. Slowly I turned, step by step I crept closer to the huge feral rat glaring at me from atop a stack of moldering portfolios. I struck, and I grabbed him, but he was too fast and escaped into the dark depths within the piles of boxes strewn about the room.

As I dusted off and opened the first of the portfolios, I was at first disappointed to find it full of the familiar photographs by Harry Burton – I had studied them all carefully at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. But then something caught my eye. At first I was not sure what it was, but with mounting excitement I realized that one of these photographs was different from its published version. The version before me of the famous photo of the mummy’s arms bedecked with bracelets showed not 8, but 9 bracelets (Fig. 1).

The background to this exciting discovery began several years ago while I was traveling in Egypt under the auspices of a generous grant from the Imhotep Foundation. [1] The story of the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb always held great fascination for me, and I was eager to use Carter’s work in the Valley of the Kings as starting point for new exploration. The discovery of the submerged ruins of Alexandria was inspirational, and I began my search for clues under water in the Red Sea. Although I did not find any significant artifacts during that search, I was fortunate enough to meet several Egyptian colleagues who shared my interests and helped me navigate the challenging logistics of archaeological research at sites in the Red Sea and throughout Egypt.

Although I felt on the verge of an important discovery, this year’s research in Egypt was beset by difficulties, from the Foundation’s fiscal problems [2] to the demonstrations in the streets of Cairo and subsequent political revolution. And yet, it was those very demonstrations that led to the subject of this paper.

I was visiting the Cairo Museum in the new year of 2011, where I presented my credentials in order to review archival documents that might aid my quest. Suddenly all within the Museum rushed out into Tahrir Square, where the mass of angry, yet soon to be jubilant, humanity was overwhelming. Left alone, fearing for the safety of the artifacts in the museum, I started searching for safe storage areas where I might be able to hide the most valuable pieces from looters. I found myself in the depths of the lowest basements, at a small storage space that seemed to have been overlooked for decades. As I opened the door, the dank smell of antiquity that escaped convinced me that no person had been in this room in recent memory. I heard voices, footsteps above, the sound of breaking glass – all I could think of was finding a safe place for the museum’s treasures. I stepped into the room and quietly closed the door. With my ear pressed against the door listening for the looters, my hand found a light switch. Pushing the switch on, a dim glow from an ancient light bulb permeated the room, and I heard an ominous scratching sound behind me. Slowly I turned, step by step I crept closer to the huge feral rat glaring at me from atop a stack of moldering portfolios. I struck, and I grabbed him, but he was too fast and escaped into the dark depths within the piles of boxes strewn about the room.

As I dusted off and opened the first of the portfolios, I was at first disappointed to find it full of the familiar photographs by Harry Burton – I had studied them all carefully at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. But then something caught my eye. At first I was not sure what it was, but with mounting excitement I realized that one of these photographs was different from its published version. The version before me of the famous photo of the mummy’s arms bedecked with bracelets showed not 8, but 9 bracelets (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The uncovered arms of the mummy, revealing a previously unknown bracelet, labeled “TT".

I soon realized that while I was searching for artifacts lost in ancient times, I had stumbled across a much more modern case of tomb tampering – that ninth bracelet has never appeared in any public documentation. Close examination of the photographs in the portfolio revealed the missing bracelet in another photo as it was carried away from the tomb by an Egyptian worker at the site. (Fig. 2). These photographs were the only evidence that this piece existed. Why did this bracelet never appear again? Could it have anything to do with those mysteries of ancient Egypt that the Foundation was created to investigate? I vowed to discover where this extraordinary piece had been taken. Gathering the photos to protect them from damage or theft, I carefully found my way out of the museum without encountering any of the looters busy on the upper floors. I returned to the rooms I had rented to study the photographs, trying to make sense of what I was seeing.

Figure 2, Detail of worker carrying the bracelet from the tomb to safekeeping.

Days later, after order had been restored to Tahrir Square, I returned there to see if I could revisit that old storeroom in the Museum. On the way, an extraordinary, miraculous event occurred. I saw a boy, surrounded by several officials, holding what appeared to be a small statue that I had seen weeks before in the museum. As I drew closer, I understood that the boy had found the statue, which was indeed a piece looted from the museum, lying in a nearby trash heap. [3] Absentmindedly thinking how odd such a situation was, I literally stumbled into another large trash heap. As I put my hand out to break my fall, it fell upon a small metallic object. Brushing away the trash surrounding it, I was astounded to see the ninth bracelet of Burton’s original photograph! How and why it got to be discarded and hidden within a pile of trash, I may never know. But fearing for its safety, I immediately brought it back to my rooms, where I could examine behind the security of my locked door.

Starting the preliminary process of photography and documentation of this remarkable piece, I saw very soon that there was more to this bracelet than I had thought. Translating the hieroglyphics inlaid into sides and bottom of the bracelet, I realized with mounting excitement that this piece was a spiritual guide for the king, containing a functional clockwork mechanism that called upon the wisdom of the ancient Egyptian gods to answer the important questions of life, as described in the following pages.

I could not resist – I carefully wound the clockwork, and asked it the question uppermost in my mind:

“Will I be able to use this discovery to help my generous sponsor fulfill their important goals?”

As I watched the scarab search for the answer, my thoughts turned to the myriad ways I could benefit mankind with such a device, when the scarab suddenly found its answer and stopped. “No.”

How could this be!? Such a wondrous and magical device must be used for the good of humanity! In the depths of despair, I fell into an oddly deep yet aware state of semi-consciousness. Perhaps it was a dream, but the memory remains vivid: My eyes were focused on the bracelet, and I heard the door to my rooms open as someone approached with a dragging, scraping sound. I saw a hand bandaged with dirty linens delicately remove the bracelet from my field of vision. Then I heard that same dragging sound receding away.

I awoke the next morning to find the door to my rooms open, and the bracelet gone. I could only think that one of the protesters, wounded in confrontations with the authorities and bandaged with whatever dirty scraps of cloth were available, had found their way to my rooms looking for something of value to sell on the black market.

With a great sense of loss, I left Cairo to record what little documentation I had assembled in those brief hours with the bracelet. The results are what you read in this paper. I can only hope that the bracelet will resurface someday, and that I will have the opportunity to address so many unanswered questions about this wondrous artifact.

Starting the preliminary process of photography and documentation of this remarkable piece, I saw very soon that there was more to this bracelet than I had thought. Translating the hieroglyphics inlaid into sides and bottom of the bracelet, I realized with mounting excitement that this piece was a spiritual guide for the king, containing a functional clockwork mechanism that called upon the wisdom of the ancient Egyptian gods to answer the important questions of life, as described in the following pages.

I could not resist – I carefully wound the clockwork, and asked it the question uppermost in my mind:

“Will I be able to use this discovery to help my generous sponsor fulfill their important goals?”

As I watched the scarab search for the answer, my thoughts turned to the myriad ways I could benefit mankind with such a device, when the scarab suddenly found its answer and stopped. “No.”

How could this be!? Such a wondrous and magical device must be used for the good of humanity! In the depths of despair, I fell into an oddly deep yet aware state of semi-consciousness. Perhaps it was a dream, but the memory remains vivid: My eyes were focused on the bracelet, and I heard the door to my rooms open as someone approached with a dragging, scraping sound. I saw a hand bandaged with dirty linens delicately remove the bracelet from my field of vision. Then I heard that same dragging sound receding away.

I awoke the next morning to find the door to my rooms open, and the bracelet gone. I could only think that one of the protesters, wounded in confrontations with the authorities and bandaged with whatever dirty scraps of cloth were available, had found their way to my rooms looking for something of value to sell on the black market.

With a great sense of loss, I left Cairo to record what little documentation I had assembled in those brief hours with the bracelet. The results are what you read in this paper. I can only hope that the bracelet will resurface someday, and that I will have the opportunity to address so many unanswered questions about this wondrous artifact.

Description of the artifact

Originally discovered on the arm of King Tutankhamen’s mummy and only recently brought to light, this bracelet demonstrates extraordinary depths of the jewelers’ art and technical abilities. Unique among ancient Egyptian jewelry, the bracelet has a hidden clockwork mechanism which enables a sculpted scarab to indicate answers to questions properly phrased.

The discovery of this bracelet with its complex clockwork mechanism is exciting not only for its combination of art and technology , but also because it demonstrates that such technology existed well before what has been considered the earliest clockwork device. The Antikythera mechanism [4] has been dated to 150 BCE, and this bracelet of King Tutankhamen predates it by about 1200 years. This should not be so surprising - the level of technology, art, and science of the Egyptian New Kingdom was close if not equal to that of the ancient Greeks who produced the Antikythera. Is it any wonder that such a civilization could produce instruments and machines of equal sophistication?

Structure

The material used for the construction of the body of the bracelet and ornamentation is high karat gold. From prehistory to the present gold has been valued as more than a rare metal, and the ancient Egyptians were no exception. With it’s disregard of the environment and resulting eternal color and surface free of tarnish and deterioration, gold was a manifestation of the sun god, Ra, on earth. Gold was strictly for the use of the nobility, and funerary articles of gold were included in the tombs of the pharaohs as a necessity for life in the after life. But this bracelet also played an important role during the lifetime of Tutankhamen, the weight and power of gold aiding the mystical scarab in its search for the truth. Careful study of various descriptive panels and wall paintings demonstrate that this particular piece had been used by Tutankhamen in his daily life to aid him – a powerful, weighty gold device to help in making weighty decisions (Figures 3 - 6).

Overall styling is reminiscent of temple architecture, with forms, proportions, and details typically found in the buildings of the New Kingdom. (Fig. 7) Constructed in two main parts, the bracelet is hinged to facilitate putting it on the wrist, with a removable pin to lock or enable opening. At these breaks in the line of the bracelet form, partial torus moldings facilitate the visual transition from bracelet body to hinge sections. Inlaid into the bracelet body, top and bottom, is hieroglyphic text. (Fig. 8 and 9)

Originally discovered on the arm of King Tutankhamen’s mummy and only recently brought to light, this bracelet demonstrates extraordinary depths of the jewelers’ art and technical abilities. Unique among ancient Egyptian jewelry, the bracelet has a hidden clockwork mechanism which enables a sculpted scarab to indicate answers to questions properly phrased.

The discovery of this bracelet with its complex clockwork mechanism is exciting not only for its combination of art and technology , but also because it demonstrates that such technology existed well before what has been considered the earliest clockwork device. The Antikythera mechanism [4] has been dated to 150 BCE, and this bracelet of King Tutankhamen predates it by about 1200 years. This should not be so surprising - the level of technology, art, and science of the Egyptian New Kingdom was close if not equal to that of the ancient Greeks who produced the Antikythera. Is it any wonder that such a civilization could produce instruments and machines of equal sophistication?

Structure

The material used for the construction of the body of the bracelet and ornamentation is high karat gold. From prehistory to the present gold has been valued as more than a rare metal, and the ancient Egyptians were no exception. With it’s disregard of the environment and resulting eternal color and surface free of tarnish and deterioration, gold was a manifestation of the sun god, Ra, on earth. Gold was strictly for the use of the nobility, and funerary articles of gold were included in the tombs of the pharaohs as a necessity for life in the after life. But this bracelet also played an important role during the lifetime of Tutankhamen, the weight and power of gold aiding the mystical scarab in its search for the truth. Careful study of various descriptive panels and wall paintings demonstrate that this particular piece had been used by Tutankhamen in his daily life to aid him – a powerful, weighty gold device to help in making weighty decisions (Figures 3 - 6).

Overall styling is reminiscent of temple architecture, with forms, proportions, and details typically found in the buildings of the New Kingdom. (Fig. 7) Constructed in two main parts, the bracelet is hinged to facilitate putting it on the wrist, with a removable pin to lock or enable opening. At these breaks in the line of the bracelet form, partial torus moldings facilitate the visual transition from bracelet body to hinge sections. Inlaid into the bracelet body, top and bottom, is hieroglyphic text. (Fig. 8 and 9)

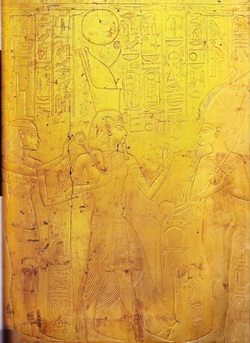

Figure 3. This chased and embossed gold panel showing the king and queen is found on the outside of a shrine that contained a gilded wooden pedestal, part of a corselet, and a bead necklace. King Tutankhamen and his wife ponder the weighty questions of the day with the assistance of the king’s bracelet. Note that the uraeus cobras of the bracelet are all facing the king, to protect and serve.

Figure 4. The gilded panel showing the goddess Isis presenting the king to her brother/husband Osiris is found on one of the doors of a shrine containing a quartz sarcophagus. The style of the representations of the bracelet differ between the two panels, as they were done by different artists, but there can be no mistaking the bracelet for other than the object of this discussion.

Figure 5. This panel from the throne of Tutankhamen shows clearly a representation of the bracelet on Tutankhamen’s wrist. Once a again, a different style by a different artisan, but an obvious reference to the bracelet.

Figure 6. A wall painting of the king, damaged by time and the elements, yet the trained eye can pick out Tutankhamen’s favorite bracelet.

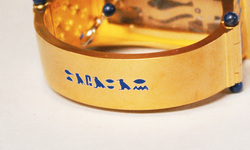

The inlays of the hieroglyphic text appear to be a substance related to faience, the use of which had been perfected earlier in the 18th Dynasty during the reign of Amunhotep III (ca. 1390 – 1352 B.C.)[6] . The blue color of these inlays complements the deep blue of the lapis lazuli balls used as end caps to the hinge and clasp. The translation of the text inlaid into the top part of the bracelet is as follows:

“Answers can be found here”

“Ask your question of the scarab”

“Seek the snake”

The translation of the text inlaid into the lower part of the bracelet is puzzling and cannot easily be translated:

“Created by (a series of hieroglyphic symbols, meaning unclear)”

Do these symbols represent one of the gods in the Egyptian pantheon? If so, it is a god as yet unrecognized. In modern times, where branding and design authorship is valued, such text would surely represent the person or business that manufactured the article. However, in ancient Egypt artisans devoted their work to their king and gods, and such vanity would be a significant deviation from the norm. Although we find other hieroglyphs hidden inside that could be an abbreviation of the artisan’s name, it seems unlikely that he would be so obvious as to claim authorship in so highly visible a place.[7] Perhaps he was a favorite of the king, and was encouraged to write his name for eternity? Research continues on this text, the results to be published at a later date.

The uppermost portion of the bracelet consists of a decorative enclosure housing a clockwork mechanism. Projecting upward from the top and forming a protective perimeter around the central scarab is a cavetto cornice with torus moldings top and bottom.[8] Such details are typical of temple architecture of the time, and they appear as finishing elements of the shrines, containers and sarcophagi in the microcosm of architectural structures found in the tomb of Tutankhamen. Beneath the cornice is a decorative frieze of stylized pendant lotus petals, and spaced a small distance below this decorative frieze is another decorative band, consisting of regular geometric forms. These purely decorative elements serve as distinct visual elements breaking up what would otherwise be a disproportionately wide area with no features to anchor and direct the eye of the observer.

Guarding the upper perimeter of the bracelet is a series of uraeus cobras. Such cobras, identified by their flared hoods, are representative of the goddess Wadjet, the protector of Lower Egypt. At the center of the uraeus array is a scarab, resting atop a dome inlaid with additional hieroglyphic text. (Fig. 10) The scarab became a symbol of the sun god Re to the ancient Egyptians because the beetle rolling a ball of dung across the ground seemed to represent the powers that caused the sun to roll across the sky. The dome of this bracelet represents the sun, both enlightening and existing under the control of the scarab mounted above. The sun god Re sees all that occurs during the light of day, and the amuletic powers of this representation assure correct answers.

Events of importance do also occur during night time, and the creators of this oracular piece have allowed for that as well. The lining of the bracelet depicts the stars of the night sky. (Fig. 13) When worn on the wrist, this representation of the night’s heavens is concealed, as are deeds done in the dark of night. In many of the tombs of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs, the ceilings of the chambers are covered with such five pointed stars. These stars are symbolic of the belief that although buried and blind beneath the earth, the pharaohs were still part of the vast and open universe. The stars within the bracelet serve a similar purpose, opening the unseen nighttime universe to the scarab above – dark deeds cannot be concealed.

The dome of the “sun” is divided equally into 8 parts, with one of three repetitive hieroglyphics centered in each part. (Fig 10) The translation of the text is as follows:

“Yes”

“No”

The third glyph repeated around the dome is the ankh. As the intent of this text was to be an answer to a question, the meaning in this application becomes clear. The ankh is the symbol of life, and all who live it know its uncertainty, with paths whose destinations can vary depending on forks taken. Most probably the meaning of the ankh on this dome is “Maybe”.

Mechanism

The metal plates serving as structure for the clockwork mechanism are pierced with symbols and hieroglyphic text, located to take best advantage of their amuletic powers.

The most visible, on the bottom plate of the mechanism, is the udjat eye, as seen through a window of polished rutilated quartz. (Fig. 11) Also known as the eye of Horus, this symbol recalls the mythic battle between Horus, rightful heir of Osiris’ kingdom, and his uncle Seth, who had murdered Osiris. During one battle, Seth tore out the left eye of Horus, but it was repaired by the lunar god Thoth and returned to Horus. It thus became a symbol of the moon, which changes over the course of each month. The right eye of Horus was associated with the sun, constant in its power and ability to see and understand. The udjat pierced into the plate is the right eye of Horus, drawing on the right eye’s amuletic power to assure that the answers given by the bracelet will be constantly true.

The middle plate bears multiple pierced hieroglyphs. In the lower left is a grouping of hieroglyphs which translate as Guide, or Leader. This could be taken as apt description of the bracelet, a guide to the truth. The lower right has a grouping of three symbols, the meaning of which is unclear, although the normally hidden nature of this plate might yield a clue. It is possible that these three symbols could represent an abbreviation of the name of the artisan – they bear similarity to the glyphs on the bottom of the bracelet, and might lend support to the theory that the artisan “signed” his work. Seven snakes complete the pierced decoration of this plate. These are representations of a cobra in repose, as differentiated from the uraeus, a cobra with flared hood. Perhaps these seven resting cobras, concealed and protected at the innermost part of the mechanism, are meant to supplement the power and strength of the uraeus cobras already guarding the scarab above. Snakes represent an important component of this bracelet, serving as guards and doorkeepers to the knowledge that the bracelet offers.

The upper plate, closest to the output of information, is pieced with a single large hieroglyph of a scarab, tying the mechanism in spirit as well as physical linkage to the scarab above. As is found in all of the plates, the metal has been pierced into multiple windows. These windows between levels of plates and components allow the spiritual powers existing within the mechanism to travel freely in their search for truth.

The components that drive the mechanism are various forms and sizes of gears, springs, and an output device resembling the modern “geneva” mechanism.[9] The gears are brass, and the shafts are an iron alloy. The shaft ends of the fastest moving gears are supported by polished stones to reduce friction, much like the modern jewels in watches. A metal spring is coiled within the first gear of the mechanism, and this causes all of the gears to rotate when the mechanism is actuated. The subsequently faster rotation of each gear finally turns a flat metal blade. This blade, in effect a fan, serves to slow down the entire series of gears, resulting in a slow and deliberate movement of the scarab. Actuation is via a linkage connected to one of the uraeus cobras guarding the top of the bracelet. The directive to “Seek the snake” is important information to impart to the user of the bracelet, as the multiple identical uraeus cobras give no indication that only one of them will actuate the scarab. Once started, the wound spring drives the gears until the scarab finds the correct answer and the mechanism stops. There is enough power in the spring to drive the process several times, and when the power of the mainspring is depleted it is restored by winding the shaft connected to the spring. This shaft protrudes through a hole in the rutilated quartz window protecting the mechanism, and winding is done with a key from below the mechanism. (Fig. 11) The key is in the form of an ankh, symbol of life, an apt form as it restores life to the mechanism. This cycle of the mechanism running out of power and “dying”, then eternally being restored to life by the ankh, is a comforting metaphor to a Pharoah who knows that his death on earth is simply passage to renewed life elsewhere.

“Answers can be found here”

“Ask your question of the scarab”

“Seek the snake”

The translation of the text inlaid into the lower part of the bracelet is puzzling and cannot easily be translated:

“Created by (a series of hieroglyphic symbols, meaning unclear)”

Do these symbols represent one of the gods in the Egyptian pantheon? If so, it is a god as yet unrecognized. In modern times, where branding and design authorship is valued, such text would surely represent the person or business that manufactured the article. However, in ancient Egypt artisans devoted their work to their king and gods, and such vanity would be a significant deviation from the norm. Although we find other hieroglyphs hidden inside that could be an abbreviation of the artisan’s name, it seems unlikely that he would be so obvious as to claim authorship in so highly visible a place.[7] Perhaps he was a favorite of the king, and was encouraged to write his name for eternity? Research continues on this text, the results to be published at a later date.

The uppermost portion of the bracelet consists of a decorative enclosure housing a clockwork mechanism. Projecting upward from the top and forming a protective perimeter around the central scarab is a cavetto cornice with torus moldings top and bottom.[8] Such details are typical of temple architecture of the time, and they appear as finishing elements of the shrines, containers and sarcophagi in the microcosm of architectural structures found in the tomb of Tutankhamen. Beneath the cornice is a decorative frieze of stylized pendant lotus petals, and spaced a small distance below this decorative frieze is another decorative band, consisting of regular geometric forms. These purely decorative elements serve as distinct visual elements breaking up what would otherwise be a disproportionately wide area with no features to anchor and direct the eye of the observer.

Guarding the upper perimeter of the bracelet is a series of uraeus cobras. Such cobras, identified by their flared hoods, are representative of the goddess Wadjet, the protector of Lower Egypt. At the center of the uraeus array is a scarab, resting atop a dome inlaid with additional hieroglyphic text. (Fig. 10) The scarab became a symbol of the sun god Re to the ancient Egyptians because the beetle rolling a ball of dung across the ground seemed to represent the powers that caused the sun to roll across the sky. The dome of this bracelet represents the sun, both enlightening and existing under the control of the scarab mounted above. The sun god Re sees all that occurs during the light of day, and the amuletic powers of this representation assure correct answers.

Events of importance do also occur during night time, and the creators of this oracular piece have allowed for that as well. The lining of the bracelet depicts the stars of the night sky. (Fig. 13) When worn on the wrist, this representation of the night’s heavens is concealed, as are deeds done in the dark of night. In many of the tombs of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs, the ceilings of the chambers are covered with such five pointed stars. These stars are symbolic of the belief that although buried and blind beneath the earth, the pharaohs were still part of the vast and open universe. The stars within the bracelet serve a similar purpose, opening the unseen nighttime universe to the scarab above – dark deeds cannot be concealed.

The dome of the “sun” is divided equally into 8 parts, with one of three repetitive hieroglyphics centered in each part. (Fig 10) The translation of the text is as follows:

“Yes”

“No”

The third glyph repeated around the dome is the ankh. As the intent of this text was to be an answer to a question, the meaning in this application becomes clear. The ankh is the symbol of life, and all who live it know its uncertainty, with paths whose destinations can vary depending on forks taken. Most probably the meaning of the ankh on this dome is “Maybe”.

Mechanism

The metal plates serving as structure for the clockwork mechanism are pierced with symbols and hieroglyphic text, located to take best advantage of their amuletic powers.

The most visible, on the bottom plate of the mechanism, is the udjat eye, as seen through a window of polished rutilated quartz. (Fig. 11) Also known as the eye of Horus, this symbol recalls the mythic battle between Horus, rightful heir of Osiris’ kingdom, and his uncle Seth, who had murdered Osiris. During one battle, Seth tore out the left eye of Horus, but it was repaired by the lunar god Thoth and returned to Horus. It thus became a symbol of the moon, which changes over the course of each month. The right eye of Horus was associated with the sun, constant in its power and ability to see and understand. The udjat pierced into the plate is the right eye of Horus, drawing on the right eye’s amuletic power to assure that the answers given by the bracelet will be constantly true.

The middle plate bears multiple pierced hieroglyphs. In the lower left is a grouping of hieroglyphs which translate as Guide, or Leader. This could be taken as apt description of the bracelet, a guide to the truth. The lower right has a grouping of three symbols, the meaning of which is unclear, although the normally hidden nature of this plate might yield a clue. It is possible that these three symbols could represent an abbreviation of the name of the artisan – they bear similarity to the glyphs on the bottom of the bracelet, and might lend support to the theory that the artisan “signed” his work. Seven snakes complete the pierced decoration of this plate. These are representations of a cobra in repose, as differentiated from the uraeus, a cobra with flared hood. Perhaps these seven resting cobras, concealed and protected at the innermost part of the mechanism, are meant to supplement the power and strength of the uraeus cobras already guarding the scarab above. Snakes represent an important component of this bracelet, serving as guards and doorkeepers to the knowledge that the bracelet offers.

The upper plate, closest to the output of information, is pieced with a single large hieroglyph of a scarab, tying the mechanism in spirit as well as physical linkage to the scarab above. As is found in all of the plates, the metal has been pierced into multiple windows. These windows between levels of plates and components allow the spiritual powers existing within the mechanism to travel freely in their search for truth.

The components that drive the mechanism are various forms and sizes of gears, springs, and an output device resembling the modern “geneva” mechanism.[9] The gears are brass, and the shafts are an iron alloy. The shaft ends of the fastest moving gears are supported by polished stones to reduce friction, much like the modern jewels in watches. A metal spring is coiled within the first gear of the mechanism, and this causes all of the gears to rotate when the mechanism is actuated. The subsequently faster rotation of each gear finally turns a flat metal blade. This blade, in effect a fan, serves to slow down the entire series of gears, resulting in a slow and deliberate movement of the scarab. Actuation is via a linkage connected to one of the uraeus cobras guarding the top of the bracelet. The directive to “Seek the snake” is important information to impart to the user of the bracelet, as the multiple identical uraeus cobras give no indication that only one of them will actuate the scarab. Once started, the wound spring drives the gears until the scarab finds the correct answer and the mechanism stops. There is enough power in the spring to drive the process several times, and when the power of the mainspring is depleted it is restored by winding the shaft connected to the spring. This shaft protrudes through a hole in the rutilated quartz window protecting the mechanism, and winding is done with a key from below the mechanism. (Fig. 11) The key is in the form of an ankh, symbol of life, an apt form as it restores life to the mechanism. This cycle of the mechanism running out of power and “dying”, then eternally being restored to life by the ankh, is a comforting metaphor to a Pharoah who knows that his death on earth is simply passage to renewed life elsewhere.

Figure 7. View of entire bracelet.

Figure 8. The upper line of text states “Answers can be found here”, the lower lines suggests “Seek the snake” and “Ask your questions of the scarab”.

Figure 9. The text inlaid into the lower part, reading “Created by (translation unknown)”.

Figure 10. Detail showing the uraeus cobra array, and the scarab, currently indicating “No”, with hieroglyphs representing “Yes” and “Maybe” visible.

Figure 11. Stars of the night lining the inside of the bracelet, with key on winding stem ready to wind the internal spring. The lower plate of the mechanism can be seen through a rutilated quartz window.

Notes to the text

[1] The Imhotep Foundation was created in 1932 after popular media of the day cast disparaging innuendo on that great architect of the pyramids. The mission of the foundation is to support studies, research, and publication that enlighten the public on ancient Egyptian life and lore. It is the Foundations hope that dissemination of this information would transcend the negative publicity regarding minor problems experienced by early archeaologists unfamiliar with procedures for avoiding curses.

[2] Due to the global recession, the Foundation was forced to cut back on even extremely important and productive research such as my own. Knowing that great success was imminent once Dr. Zaniya and I continued our work from the previous year, I offered to pay all expenses out of my own pocket if I failed to bring new and important discoveries to light.

[3] As reported by Kate Taylor in the New York Times, February 17, 2011: “Stolen Egyptian Statue is Found in Garbage”

[4] The Antikythera mechanism was discovered around 1900 in a shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera. It is a complicated gear driven computer, and the science, technology, and craftsmanship it demonstrates would not be seen again in extant works for another 1000 years. Its function appears to have been to plot the positions of celestial bodies up to nineteen years into the future.

[6] Faience was made of crushed quartz or sand, with small amounts of lime, and either natron or plant ash. After firing, various of a wide variety of colors were applied to give the brilliant colors the Egyptian artisans were able to achieve. Alternately, these inlays could be created with the technique of mixing fine colored ceramic particles in a binder, or firing glass frit, other techniques developed during the time of Tutankhamen. The deep blue color mimics lapis lazuli, a stone widely used in works created for the king and his court and prized for its intense blue color

[7] Zahi Hawass relates in his book, King Tutankhamen, the Treasures of the Tomb, Thames and Hudson, Inc. 2007, that at an excavation at Giza of a tomb belonging to a priest named Kai, he found that the master artisan had secretly signed his name under one scene

[8] Dieter Arnold defines in his book The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture , L.B.Taurus & Co. Ltd, 2003:

The cavetto cornice of ancient Egypt is derivative of the customary practice of planting palm fronds in a row along the tops of walls. Torus moldings form the finishing edges along the vertical or horizontal edges of buildings, and possibly derive from the protective edges of bundles of reeds or the corner posts of early structures supported by bricks or wooden mattes.

[9] A geneva mechanism converts constant rotary motion into indexed rotation with obvious pauses between indexed locations. This causes the scarab to move from position to position, pausing briefly at each position as if contemplating if that is the correct answer.

Video by Digi-Do Media Productions.

Music provided by www.freeplaymusic.com.

End – as told to S. Parker.

Copyright 2011 Steven Parker

[1] The Imhotep Foundation was created in 1932 after popular media of the day cast disparaging innuendo on that great architect of the pyramids. The mission of the foundation is to support studies, research, and publication that enlighten the public on ancient Egyptian life and lore. It is the Foundations hope that dissemination of this information would transcend the negative publicity regarding minor problems experienced by early archeaologists unfamiliar with procedures for avoiding curses.

[2] Due to the global recession, the Foundation was forced to cut back on even extremely important and productive research such as my own. Knowing that great success was imminent once Dr. Zaniya and I continued our work from the previous year, I offered to pay all expenses out of my own pocket if I failed to bring new and important discoveries to light.

[3] As reported by Kate Taylor in the New York Times, February 17, 2011: “Stolen Egyptian Statue is Found in Garbage”

[4] The Antikythera mechanism was discovered around 1900 in a shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera. It is a complicated gear driven computer, and the science, technology, and craftsmanship it demonstrates would not be seen again in extant works for another 1000 years. Its function appears to have been to plot the positions of celestial bodies up to nineteen years into the future.

[6] Faience was made of crushed quartz or sand, with small amounts of lime, and either natron or plant ash. After firing, various of a wide variety of colors were applied to give the brilliant colors the Egyptian artisans were able to achieve. Alternately, these inlays could be created with the technique of mixing fine colored ceramic particles in a binder, or firing glass frit, other techniques developed during the time of Tutankhamen. The deep blue color mimics lapis lazuli, a stone widely used in works created for the king and his court and prized for its intense blue color

[7] Zahi Hawass relates in his book, King Tutankhamen, the Treasures of the Tomb, Thames and Hudson, Inc. 2007, that at an excavation at Giza of a tomb belonging to a priest named Kai, he found that the master artisan had secretly signed his name under one scene

[8] Dieter Arnold defines in his book The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture , L.B.Taurus & Co. Ltd, 2003:

The cavetto cornice of ancient Egypt is derivative of the customary practice of planting palm fronds in a row along the tops of walls. Torus moldings form the finishing edges along the vertical or horizontal edges of buildings, and possibly derive from the protective edges of bundles of reeds or the corner posts of early structures supported by bricks or wooden mattes.

[9] A geneva mechanism converts constant rotary motion into indexed rotation with obvious pauses between indexed locations. This causes the scarab to move from position to position, pausing briefly at each position as if contemplating if that is the correct answer.

Video by Digi-Do Media Productions.

Music provided by www.freeplaymusic.com.

End – as told to S. Parker.

Copyright 2011 Steven Parker